The less I believe in God, the more sacredness I experience

Against fixed beliefs

I was reading this insightful column by Kwame Anthony Appiah over the weekend and was struck by the difficulty of defining what a religion is:

When the term “religion” settled into its now-familiar usage, around the 17th century, it reflected Protestant assumptions, emphasizing belief, individual conscience and voluntary association.

…

None of these definitions, or any other, won the day. If you follow many disciples of Durkheim, religion can look like almost any system that supports social cohesion and provides psychological comfort — at which point patriotism or even psychoanalysis can slip into the category. If it involves spiritual beings, it leaves out Buddhism in its more austere forms. If, as the anthropologist Clifford Geertz proposed, religion is a “system of symbols” establishing powerful moods and conceptions of a “general order of existence,” it’s hard to say why nationalism or Marxism doesn’t qualify.

The definitional perplexities are as persistent as ever.

I want to deemphasize beliefs as statements about the world—and the picture of religious life that comes with them. A quick note on how I’m using “belief.” There are two kinds of belief: propositional and practical (“as if”). I argue we don’t need the propositional kind1; the practical kind does the work.

This idea that belief is central to what it means to be part of a religion, as Appiah notes, is a Protestant idea. And yet many of us non-Protestants, marinating in Western culture, have unwittingly accepted the centrality of belief. Much to our detriment. In both of the spiritual traditions I’m part of, Judaism and Buddhism, belief is much less central than in this Christian perspective.

Judaism can be seen as a religion concerned with unifying a diasporic people. Beliefs can do that, but so can a shared community of practice, bound by law. During one of my recent re-encounters with Judaism, I was speaking with a renewal rabbi about my ambivalence toward participation and toward the halakhic way of life more generally. His reply, with laughter, was that such feelings were “the most Jewish thing ever.” I also met an Orthodox Jewish professor who does not believe in God but still practices because of the deep connection to the traditions. When the Hebrews received the Torah, they said “Na’aseh v’nishma” (נעשה ונשמע), usually rendered “we will do, and then we will understand.” In other words, action comes first.

Buddhism is, likewise, more a set of practices than a set of beliefs. When you take a view in a meditative practice, it’s more like “as if” than making a strong metaphysical commitment. In the sutras, the Buddha generally eschews metaphysical pronouncements. In Tibetan Buddhism there is a well-known debate, shentong versus rangtong. Very roughly, rangtong treats the ground as empty and insubstantial all the way down; shentong takes the luminous, loving, fecund quality of awakening as pointing to something absolute. Rather than give an answer one way or another, this is seen to be an irresolvable practice tension, and we are meant to avoid the nihilism or fundamentalism that either pole would lead us to on its own.

What’s remarkable about that practice tension is that holding it actually has an experiential effect, namely that the more I see reality as empty, insubstantial, the more my direct experience is one of radiance, of living in a sacred world. Another paradox to chew on.

Scientifically we can also ask whether we have any beliefs whatsoever. I am reminded of a classic paper I read in graduate school written by a professor of mine, Baruch Fischhoff, provocatively titled, “Value Elicitation: Is There Anything In There?” In the paper, Fischhoff contrasts the view that humans have a broad range of well-defined values (articulated values) that we can elicit versus the view that humans have only a few values and they have to re-derive or figure out what’s important given a novel set of questions. Psychologist Nick Chater also wrote a book about this, The Mind is Flat, where he argues that people have very few articulated values (and maybe not very many basic ones either).

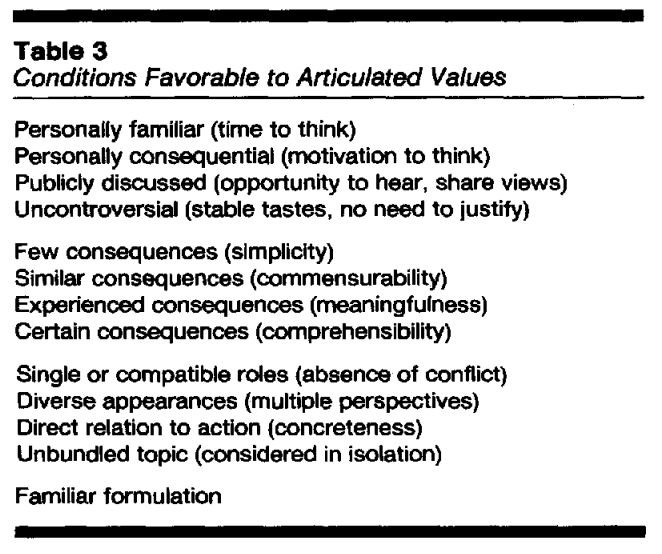

Of course this sits on a continuum. My belief that there is a laptop in front of me is more well-defined than my belief about what really happened in my marriage. Fischhoff has a helpful list of conditions under which values are easy to articulate: personally familiar and personally consequential; publicly discussed and relatively uncontroversial; with few, similar, experienced, and fairly certain consequences; when one is acting in a single role without conflict; when there is a direct tie to action; when the topic can be considered on its own; and when the framing is familiar.

Looked at through this lens, metaphysical beliefs fail most of these at once. They are controversial, their consequences are many and hard to compare, feedback is sparse (or non-existent), the tie to concrete action is opaque, and they come bundled with other claims. By contrast, practice-laden values often meet these conditions: they are concrete, repeatedly experienced, discussed in community, and they provide feedback you can actually feel.

Even if metaphysical beliefs could be made crisp, it’s not clear why we need them. What matters in practice are values in the live sense: the convictions that shape attention and action. Not a catalog of abstractions, but the felt priorities that give practices bite. You can live Shabbat as if it matters and watch your attentional capacities change. You can take the Bodhisattva vow as if it’s real and notice your habits bend toward care. Practice guided by clear values yields belonging, transformation, and awe without requiring fixed metaphysical commitments. The conviction is doing the work, even when the propositions are nebulous.

I’d previously addressed this question more practically in describing how to practice rituals effectively.

There's a classic psychology experiment (that I believe has survived the repeatability crisis) where you set up experimental situations where you trigger an action in people, without them realizing it. When you ask them why they carried out the action, they will almost always provide a logical explnation for what they did, which is completely false. In other words the linguistic circuits of our brain are very good at justifying our actions, on the basis of very little data.

As humans we don't have reflective access to our decision making process at a linguistic level, so when asked to account for our behavior and justify it, we will tend to draw upon the resources that we have available to us. Moral texts, cultural values, etc. And we may believe those texts, but there's no particular reason to think that they will inform our behavior, unless we are taking practical action to enact those values. They're maybe better thought of as socially acceptable excuses :)

> Even if metaphysical beliefs could be made crisp, it’s not clear why we need them.

Well perhaps they're an effective way of structuring and guiding our practices and rituals. Would the Bodhisattva vows have come into being without the metaphysical beliefs of Buddhism underpinning them? And perhaps those vows are more effective if you believe (or more accurately - commit to) the ideas of Buddhism. And if the practices work, but the values have become nebulous, then maybe the trick is to find new values that support those practices. Though as how to do that effectively...

Two footnotes:

1) Orthodoxy (right belief) vs. Orthopraxy (right conduct) is how academics frame the distinction between Protestantism and Judaism/Buddhism you highlight.

2) Ju Mipham suggested an interesting reconciliation of Rangtong and Shentong:

Phenomenological Emptiness (shentong) can be reified. Analytical Emptiness (rangtong) is the antidote to this.

Analytical Emptiness (rangtong) ignores the experience of emptiness. Phenomenological Emptiness (shentong) is the antidote to this unseeing.

Together, they offer mutual corrections even as they spawn their own errors.